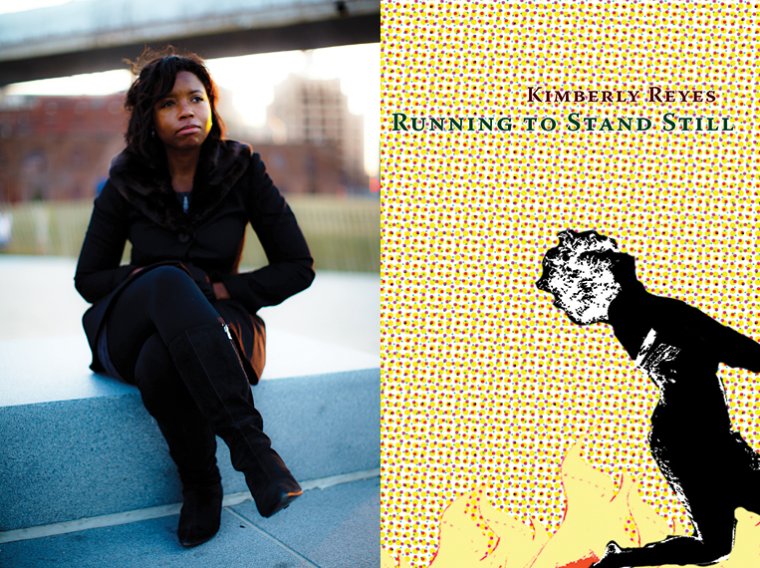

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Kimberly Reyes, whose debut poetry collection, Running to Stand Still, is out today from Omnidawn. Rich in literary and pop culture references, the voice of Running to Stand Still is both specific and wide-ranging. Quotations from artists as disparate as Frank Bidart and The Killers splice and introduce poems. In one section, Reyes repurposes screenshots of text messages; in another, partial strikethroughs enable multiple readings. Through this juxtaposing of different forms and language, Reyes weaves a deeply intimate portrait out of impossibly expansive themes: modern life, Black womanhood, family history, and technology. “The brilliance of these poems is their achievement of discomfit as they simultaneously travel distance and move inward,” writes Valerie Wallace. Kimberly Reyes is also the author of a poetry chapbook, Warning Coloration (dancing girl press, 2018), and a collection of essays, Life During Wartime (Fourteen Hills, 2018). Her poems have appeared in Columbia Journal, Cosmonauts Avenue, and New American Writing, among other publications. A second-generation New Yorker, Reyes is currently a Fulbright fellow studying Irish literature and film at University College Cork in Ireland.

Kimberly Reyes, author of Running to Stand Still.

1. How long did it take you to write Running to Stand Still?

All in all, about five years. I didn’t know the collection would become a book as I was writing the early versions of the poems that appear in the first few sections. But those poems became the chapbook Warning Coloration. That’s when I really started to see a narrative that I knew I had to do justice to in book form.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Sitting with and then ultimately bypassing the fear of what others might think. The book is a lot about the external gaze, and it’s no secret (if you’ve read the book) that I’ve had a problem with prioritizing other people’s opinions about me over my own for a long time. It’s a tough habit to break.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Honestly, not nearly enough. I’m in that loop of applying for fellowships, scholarships, and grants so that I can write, but then the next application cycle comes around and I need to be applying again instead of writing. I also might have some undiagnosed case of ADHD or maybe we are all just a bit frazzled with the state of the world today, but it’s not always easy to sit and focus. When I do find time to write, it’s like I’m back to myself. I’m back home. And that currently happens once a week or so. When I lived in San Francisco I lived in a heavenly cottage that had a half room with a loft and a big, garden-facing window so I would use that space as an office and write there. Now, as a Fulbright fellow in Cork, Ireland, I usually write upstairs in my bedroom, on my bed, using my nightstand as a desk, staring at the rain, and I feel just as productive.

4. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

It depends if it’s poetry or prose, but for poetry my dear friend Irène Mathieu. We were roommates as Callaloo fellows, and she’s just a brilliant writer and reader of poetry—honest, sharp, and hilarious. For prose I don’t send out anything of importance without first sending it to a friend I’ve known since junior high school, Rachel Sur. She pulls zero punches and that’s precisely what I need, especially because so much of my writing deals with sensitive subjects. The work has to be done honestly and correctly, and she definitely has my back as far as that’s concerned. Our thirty-year friendship means that she knows when I’m bullshitting before I even do.

5. What are you reading right now?

I just finished reading Kiese Laymon’s Heavy, and whew, no kidding. Whew. What an amazingly raw and honest and beautiful and insightful work. That’s the kind of book that helped me sit down for my weekly writing session and just have at it. It’s a call to art, so to speak. It’s an example of the kind of honesty and reflection that can heal us.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Oh man, how to even begin? I won’t point out anyone in particular. I’ll just say people outside of the MFA networking world. I love reading the slush-pile success stories.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

I went through a round of edits with Rusty Morrison that was everything I wanted it to be. She started by saying: We can publish this manuscript as is now, that’s fine, it’s a good book, but let’s make it great. I loved that artistic faith and freedom.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Running to Stand Still, what would you say?

Don’t work with people who don’t respect you or your art. Publication isn’t worth that sacrifice. You put too much blood on the page to have something in the world that doesn’t feel professional. I learned that lesson the hard way with the project right before this book. I will revisit that project and make it what it should be, but the time and energy that incarnation of it took away from me… I’m not sure it was worth it. Working with Omnidawn was healing and affirming and this book is my true firstborn.

9. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

The networking, marketing machine. I talk about how socially awkward I can be all the time and I’m certainly not the only writer with that affliction and I just think the publishing community I know isn’t very tolerant of that. So many of our favorite writers were absolute recluses and we loved them for that, yet they wouldn’t be published nowadays. I like having my reclusive moments, and while it may not be good for my career it’s certainly good for my writing.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I think it was: Don’t read writers you don’t like. I can’t actually remember who said that but that sentiment was transformative for me because we are taught, especially in MFA culture, to slog through writing we don’t necessarily feel because it’s a good exercise in reading and expanding our horizons. But there’s way too much stuff out there to be moved by and to enjoy instead of wasting time with a backlog of books you loathe. It’s important to challenge yourself and to branch out, but life’s too short and there aren’t enough hours in the day for that kind of pain.