I first encountered Laura van den Berg’s work at a reading, and her words entranced me. The piece she read, an excerpt from her debut novel, Find Me (FSG, 2015), compelled me viscerally yet felt eerily dream-like; it raised the hair on the back of my neck. Surely, I thought, this must be the result of her commanding stage presence. But no. On the page, van den Berg’s voice is just as striking and magical.

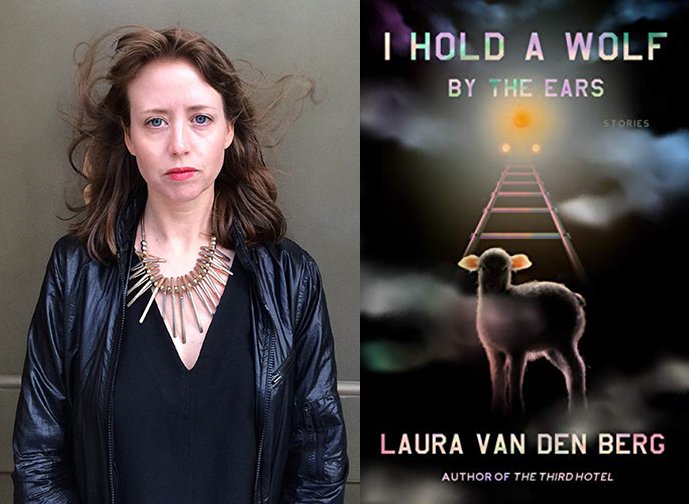

Laura van den Berg’s latest book, the story collection I Hold a Wolf by the Ears, is out now from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

In her new collection, I Hold a Wolf by the Ears, out now from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, van den Berg returns to the short story after her acclaimed sophomore novel, The Third Hotel (FSG, 2018). In an essay that accompanied the galley, she writes that short stories saved her life, providing her new passion and hope when she first encountered one at the age of eighteen, on the verge of flunking out of college. At the time, she knew so little about literature that she called the stories “tiny novels.” In the case of her work, the term is apt. Each of the eleven pieces in Wolf is as sharp as a fang, but the stories’ shadowy margins hint at a wide—and wilder—world beyond their borders. In “Lizards,” a woman enraged by the politics of the day finds comfort in a generic brand of seltzer her husband supplies her, a drink that anesthetizes her, and that she comes to appreciate because being asleep is preferable to being angry. In “Hill of Hell,” a woman who has a stillborn baby finds herself replaying a similar scene years later, when she has another daughter who dies of a tumor. The women in these stories live in a cruel world, and throughout there is a sense of something otherworldly—ghosts, or if not ghosts, strange, unseen forces—at play.

Over e-mail, I had the pleasure of talking with van den Berg about her collection. As we did, a strange mirroring happened. Unseen forces took shape as the pandemic put our world on hold. We found ourselves in a weird, fraught limbo where the line between life and death is tenuous—a fitting feeling, it seemed, for discussing her uncanny work.

Of putting together this collection, you write: “When I sense that I might be working my way toward a collection, I am mindful of where the stories begin to overlap, to speak to one another, and before long I could discern a recurring thread: All these stories were ghost stories, in one way or another.” Can you unpack this for me? I’m curious about the act of composing the collection as a whole, and what decisions were involved.

The composition of Wolf was a little unusual in that, at one point, I had maybe seventeen or eighteen stories that were “candidates” for a collection. Yet I understood that these stories did not all belong in the same book. But what was the book? I had to spend a lot of time thinking through that question. And then, in the summer of 2018, I spent nearly six weeks at a residency and wrote four new stories: “Hill of Hell,” “Cult of Mary,” “Karolina,” and “Your Second Wife.” The addition of these four was hugely clarifying, in that I could now identify the stories that wanted to be in conversation with one another, could see the recurring thread of the “sideways ghost story.” I pulled my six favorite haunted stories out of the big preexisting stack. Then I had ten. After working on the order for a while, I sensed that a beat was missing and wrote “Lizards,” the most overtly topical of the stories, last.

I love that phrase, “sideways ghost story.” What do you mean by that?

I’m thinking about ghost stories that are a bit unconventional, or/also that are coming at the haunted from an unexpected angle. In some stories in Wolf, the hauntedness is literal, as in: ghosts! In other stories, the haunting is more a state of being, both in the self and in the surrounding world.

“Lizards” stands out in how topical it is: It’s set during what seems to be Brett Kavanaugh’s Senate hearing, although he goes unnamed. How has your work changed over time in regard to its engagement with politics? And why did you think the collection needed a story that contained a reference to this administration?

Parul Sehgal has a great essay called “The Ghost Story Persists in American Literature. Why?” There she describes ghosts as “social critiques camouflaged with cobwebs.” I was thinking a lot about the supernatural as a conduit for exploring the ways in which the worlds of these women are designed to cause erasure and harm. I’m equally interested in the supernatural as a conduit for exploring how some of these women also cause erasure and harm, especially in the wake of the 2016 election and given the role white women played in it. This perhaps comes out the most in “Karolina,” but it’s present in “Lizards,” too, I think. On the one hand, the wife is furious over Kavanaugh. On the other, what is she willing to do to challenge the structures that make someone like Kavanaugh possible?

As a younger writer, I was raised with the idea that art should not be too explicit with its politics, lest we become blunt or polemical. We weren’t told to be apolitical exactly, but subtlety was prized. I will always deeply believe that fiction is most powerful when we are writing in the direction of the unknowable and when forgone conclusions are being disrupted, but I no longer believe that project to be at odds with also having a political vision for one’s work.

In those two stories, “Lizards” and “Karolina,” the political dimension is most explicit, but male violence—whether physical, like in “Volcano House,” in which the protagonist’s sister has been killed at a mass shooting by a young white man, or psychological, like in “Cult of Mary,” with its aggressively overbearing older white male tourist—is a specter plaguing many of the protagonists in Wolf. I found it powerful to consider the way the house that we all live in, this country, is haunted by the violence of white men.

Yes, it is. That’s not a new reality, but it is one that was weighing heavy as I worked on Wolf. My ambition was not to render that dynamic in a simplistic way—villain vs. victim—but rather to explore the various kinds of power structures at work in the daily lives of these characters (and their varying degrees of complicity with them). “Your Second Wife,” for example, concerns a gig worker who has devised a gig that allows her to do relatively well in this economy and also makes her extremely vulnerable to harm.

This brings to mind the title story, in which the protagonist is both a victim of male violence — she’s slapped in the face by a man who runs around town slapping women at random — and at one point she herself slaps a man in the face, a man whom she then allows to help her. It’s complicated, so much so that by the end of the story she is no longer sure who exactly she is. Why did you choose that story as the title of the collection?

Well, the original title was “Aftermath,” but that story got cut. Then I wasn’t sure what the title should be. My friend Lauren Groff was an early reader and she is really gifted at structure. I’d asked for her input on the order, and she replied with a complete re-imagining of the order I had given her. I was so grateful. Her argument for putting “I Hold a Wolf by the Ears” last was that the story has the most of the other stories’ elements in it, so it brings about a kind of thematic culmination (I’m paraphrasing). In thinking about this more, I also like that the story ended on a moment of expanse, of mystery and wonder and opening up. Thinking about the order, in turn, clarified why that story was destined to be the title story.

Was there a typical way in which these stories came to you, or that you found your way into them? Formally, they are very different from one another. You mentioned “Hill of Hell,” for instance. It opens with a relatively contained scene of two old friends talking on a train, and then, in the course of pages, years pass, then a whole lifetime. I was so taken by the sweep of this story.

I had such a hard time with my first few drafts of “Hill of Hell” because I was trying to make the whole story happen on the train. And the whole story did not want to happen on the train. Then I was reading Yiyun Li’s “Gold Boy, Emerald Girl,” and Denis Johnson’s “The Largesse of the Sea Maiden,” and was reminded that time need not be linear and compact in stories. It can be vast, broken, and capacious in unusual and surprising ways. Not a new concept, but one that I needed to be reminded of at that particular moment and one that allowed me to write the story. So sometimes I have an idea or approach that’s a bit right-headed and a bit wrong-headed and I find my way through reading. Sometimes it’s the frequency of a certain voice [that leads me], or I get very interested in a situation or a concept. The portals appear in many different ways, I find.

A hotel is of course central to The Third Hotel and here hotels appear in “Volcano House” and in the title story. They bring to mind the similar backdrops in Katie Kitamura’s A Separation, or the work of Stefan Zweig, or John Irving’s The Hotel New Hampshire—a whole class could be built around literature set in hotels. Why have you returned to that setting so often? And what else could be added to the reading list of this imaginary class?

I would love to teach or take such a class. Maybe I will! I would add Juan Villoro’s The Reef, which takes place at the Pyramid, a resort that specializes in “extreme tourism,” and Joanna Walsh’s Hotel, which chronicles Walsh’s experiences as a hotel reviewer. Hotels contain a great many interesting and bizarre intersections. They bring together groups of people who might never congregate otherwise. These are anonymous. They are intimate. There are layers of access and privilege. Depending on the hotel, it might be designed to be so extensive and labyrinthian that one never has to leave, almost like a stranded cruise ship. I think fiction thrives on contradictions, and hotels tend to be full of them.

On Literary Hub, in a conversation with Crystal Hana Kim, you said that you were working on some of these stories in tandem with The Third Hotel. This isn’t surprising, given that The Third Hotel begins when the protagonist, Clare, sees her recently deceased husband while traveling in Cuba—another ghost. I’m curious how this worked, process-wise. Did you sometimes put aside the novel to pen stories, or did the stories happen in the margins while waiting for readers to give you feedback on drafts, or during the long road to publication? And what connective tissue do you see between the two books?

Well, I was at that residency that I had mentioned, after I had finished The Third Hotel but before it was published, so hauntedness was—and is—still very much on my mind. The oldest story I wrote in maybe 2013 or thereabouts, before I started work on the novel, but others were written alongside The Third Hotel. If I’m remembering correctly, I wrote a burst of stories near the end of a very intense phase of revising, as though my imagination was in desperate need of an escape hatch, a chance to dream in different directions, after spending so much time in Clare’s claustrophobic world.

On Twitter, you shared a syllabus for a class about ghosts stories you were teaching. Are any of these stories in conversation with those?

Yes, definitely! I think there is a very physical dimension to hauntedness, in that it often has to live somewhere tangible. “House Taken Over” by Julio Cortázar and some of Mariana Enriquez’s stories, like “Adela’s House” and “The Dirty Kid,” got me thinking about movement through physical space as a passage from one dimension to another. I also am interested in hauntings of a more ambiguous sort, like the kind in Helen Oyeyemi’s story “Presence” or in Joy Williams’s “The Country.” In my “haunted” class, we read Freud’s “The Uncanny” and spent time with the idea that the uncanny is connected to matter that is supposed to be kept secret being inadvertently revealed—and how that can be a powerful energy source for a work of fiction.

I love that “uncanny” element in your work so much, Laura, and would love to be a fly on the wall in that class. How did you learn how to channel that energy source in your work? What advice do you have for a writer who wants to do something similar?

In that class, we talked about how, when it comes to the supernatural, the more important question is not “What is it?” but “Why is it?” Not with the idea that the why should receive a definite answer, but rather thinking about how the latter question can be a powerful generator of urgency and surprise and meaning.

For me, the most powerful hauntings in literature are deeply rooted in histories both macro and micro. What are the supernatural elements here to show us? What questions are they here to ask? What directions are they encouraging us to look in? What histories do they want us to consider? That said, I don’t think about any of these questions when I’m just starting out; these are all post–first draft considerations. Steven Millhauser describes stories as “visions,” and for me those early drafts are very much about transcribing the initial vision. Everything follows from there.

I feel like I would be remiss not to mention the backdrop against which we’re having this conversation. What has this time of pandemic and quarantine been like for you as a writer, both professionally and also creatively? Politically, if you allow yourself to dream, what do you hope might change after this crisis?

I feel like there is very little perspective right now. Or at least I have very little perspective to offer. For writers, people compelled to make stories, it can be tempting to approach catastrophe as an occasion for narrative. In many ways, this is a very natural and human impulse. A narrative can lend an experience a comprehensible shape. A narrative can help us find meaning. Yet there is nothing intrinsically meaningful about what’s happening. A virus is not a metaphor, or inherently instructive. This period of time does not have to be an occasion for insight, let alone wisdom. So more than anything I’ve been trying to just remain alert to the bewildering present tense, which is evolving in frightening ways day by day.

Publishing is now facing unprecedented challenges. Apart from cancelled tours, it’s uncertain how much longer houses will be able to print and distribute finished copies of books. Of course, everyone—agents, editors, writers—are doing their level best to innovate, with much nimbleness and creativity, but I don’t think anyone really knows what the future holds. Everything, from the fate of certain industries to the health of one’s immediate community, is tenuous right now. One thing that is certain: I am grateful every day for the wonderful team I work with. This is a strange and unsettling road, even for someone who has published four books, but I have some incredible traveling companions.

Strangely I have been able to write—at least for now. I think it might be because I’m working on a project set in the world of women’s amateur boxing and I miss my own gym terribly, so sheer longing has been calling me to the desk. Also, the boxing world can be a hermetic one in certain ways, which is maybe why it’s a space that feels possible to access on the page.

I hope the pandemic shatters any lingering illusions about this country’s relationship to equality and justice. We were ill-prepared for a catastrophe of this magnitude, and the longer it unfolds the more the inequity that is deep in the marrow of our systems is revealed. My political dream would be to elect leaders who are committed to creating a better reality for all, as opposed to just doing triage on the one we have.

Brian Gresko is a writer based in Brooklyn, New York, and the editor of When I First Held You: 22 Critically Acclaimed Writers Talk About the Triumphs, Challenges, and Transformative Experience of Fatherhood. You can find him online hosting The Antibody, a virtual reading series started during quarantine, and at briangresko.com.