When University of Virginia (UVA) professor Andrew Stauffer sent his class to the library in the fall of 2009, he expected them to focus on the printed text of the books they brought back. But Stauffer and his students soon realized that was just one story being told in these volumes. While looking at nineteenth-century copies of work by Felicia Hemans, a poet wildly beloved at the time for her sentimental verse, the students were immediately drawn to everything else happening in these books: not just the expected underlining and dog-ears, but bookplates, diary entries, letters, quotes, pressed flowers, and readers’ own poetic flights of fancy. One reader had even penned an elegy for her daughter Mary, who had died at age seven. What they found in the Hemans books “opened our eyes,” Stauffer says. “It suddenly clicked. This wasn’t noise or damage—this was augmentation.”

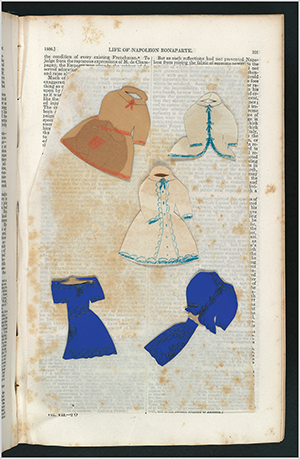

Doll clothes pressed into an 1833 book. (Credit: Image courtesy of the University of Virginia Library Digital Production Group)

In 2014, Stauffer founded the Book Traces project to investigate what else the library might be hiding in plain sight. He started an online archive of his findings at booktraces.org, and has since invited anyone from around the world to submit photographs of the “traces” they find in library books published before 1923—meaning books that are in the public domain—in circulating collections.

Interested in formally expanding the project, Stauffer and Kara M. McClurken, the library’s director of preservation services, successfully applied for a grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources. He recruited Kristin Jensen to manage the project and hired research assistants to comb through thousands of books on the open shelves of UVA’s libraries and catalogue the extra material the books yielded.

What they found went far beyond expectations. Traces were everywhere. “We realized there was a whole hidden collection within the collection,” says Jensen. Readers from the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, it turned out, used books as souvenirs, journals, greeting cards, funeral programs, and invitations, among myriad other purposes. And while scholars such as Leah Price have long observed the many uses Victorians had for their books, Book Traces researchers were astonished by the breadth and depth of annotations, insertions, marginalia, and inscriptions right in front of their noses. And all this material was unsorted and undocumented—when any one of these volumes got deaccessioned or shifted off site, these traces could vanish forever.

Stauffer had a hunch that if this much material was in UVA’s library, then there was more to be found elsewhere, and the project expanded to invite contributions from more institutions. Today, Book Traces extends to schools from Arizona State University and Bryn Mawr College, and has documented more than three thousand traces, including a sketch of a woman breastfeeding a baby in The Story of a Beautiful Duchess; a ticket labeled “Admit Bearer” in The Spirit Messenger, a nineteenth-century spiritualist text; a tracing of a schoolgirl’s hand in a copy of The Works of William Shakespeare; and annotations in Longfellow’s Poems and Ballads that detail when and where a woman read the marked lines with her long-lost lover. One of Stauffer’s favorite finds—doll clothes pressed into an 1833 copy of Sir Walter Scott’s The Life of Napoleon Bonaparte—appears on the cover of Book Traces: Nineteenth-Century Readers and the Future of the Library, his book on the project forthcoming from the University of Pennsylvania Press in January 2021.

Rare-book historians have long studied the marginalia of famous readers—a volume of Montaigne’s writings believed by some to have belonged to Shakespeare may suggest that the Bard lifted not just ideas, but also direct phrases from the famous essayist, and the books in Newton’s and Dickinson’s libraries testify to their influences. Book Traces, on the other hand, shows how everyday readers interacted with books and how physical copies of the same work could wildly differ depending on its readers. The extra material also often reveals families of books, or books that once belonged in the same library but have since been scattered across several institutions.

In this way Book Traces celebrates what Stauffer calls bibliodiversity: appreciating each book as its own object with its own life and history. “We’re fighting against the idea that once you’ve digitized a single copy, then you don’t need others,” says Stauffer. However, Jensen and Stauffer stress that Book Traces is hardly antidigitization: On the contrary, the project would not be possible without technological tools. Book Traces comes at a pivotal moment when many libraries, pressed for resources, find themselves shuttling books off site and deaccessioning swaths of their collections. The kinds of books that typically go first are the ones at the heart of Book Traces: circulating books on the open shelves but not rare volumes, and not ones belonging to important historical figures. Stauffer and Jensen’s goal is to have a mechanism in place for all libraries to sift through the collections and discover what traces might be lurking in their copies. Of course, Jensen concedes, libraries have to make compromises since there’s a finite amount of physical space and new books keep coming in—and a global pandemic has made scholars increasingly reliant on digital texts. “We’re not saying you have to leave every single physical book in place,” Jensen stresses. “But you have to consider each as a unique artifact with a history.”

During the COVID-19 crisis, of course, physically collecting new data is impossible. But Book Traces is as busy as ever. Stauffer and Jensen are working with machine vision researchers to streamline the process of searching for traces: By noting patterns across the data, they hope to be able to figure out what types of books might yield traces and where physically in the books readers were likely to make their marks.

And even when students can’t get into libraries, Book Traces gives students the chance to do original research. The project still has thousands of pages scanned that haven’t been transcribed, which Stauffer and Jensen see as a potential gold mine for students in cultural history, an opportunity to get up close and personal with historical documents right from their computers, training them in the art of literary detective work. “It’s not a canned practiced experiment,” says Jensen. “We really don’t know what’s out there. It’s up to them to discover it.”

Adrienne Raphel is the author of Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures With Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them (Penguin Press, 2020) and What Was It For (Rescue Press, 2017).