Garth Greenwell isn’t interested in creating literary heroes. “There is a kind of luxury in narratives where the moral calculus is clear. I think it’s one of the reasons why we’re still so addicted to World War II dramas,” he says. “That was the last moment where we felt like the good guys and the bad guys were really obvious. But we don’t live in a world like that and we don’t inhabit selves in which goodness and badness are clear.”

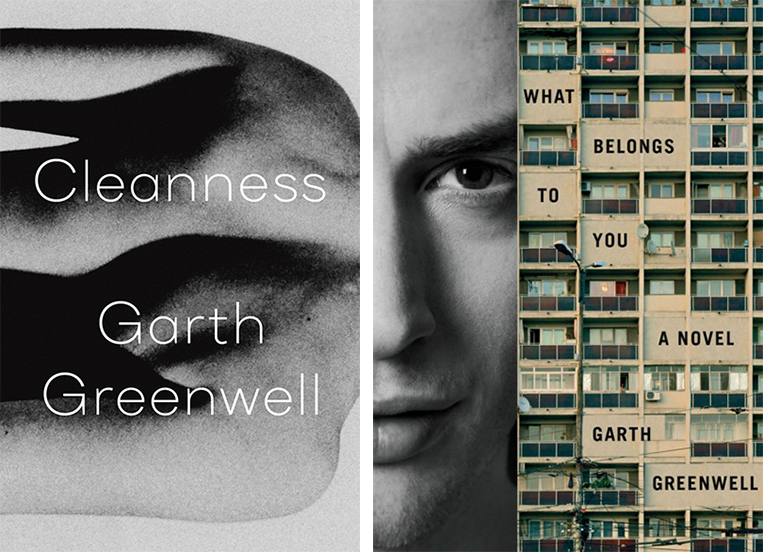

Garth Greenwell, author of Cleanness and What Belongs to You. (Credit: Bill Adams)

There is perhaps no better example of Greenwell’s love of moral complexity than his wildly successful debut novel, What Belongs to You (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016), which was long-listed for the National Book Award, named one of the best books of the year by more than fifty publications, translated into a dozen languages, and hailed as an “instant classic” by the New York Times Book Review. Though it is a work of fiction, What Belongs to You was, in part, inspired by Greenwell’s four-year stint as an English teacher at the American College of Sofia in Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013. The book explores a relationship between an unnamed, closeted American narrator teaching English at a high school in Sofia and his lover, Mitko, a young, broke, local hustler whom the narrator picks up in a public bathroom. What on its face might have seemed like a narrative of clear “moral calculus” was, in fact, a deeply nuanced exploration of sexuality, class, and citizenship.

But as Greenwell worked on What Belongs to You he kept having to set aside characters and storylines that fell beyond its scope. His new novel, Cleanness, out now from FSG, returns to the world of the narrator but allows readers a much fuller picture not only of his life but that of the citizens of Sofia and their dual struggle for identity and purpose. “It’s not like one book is a sequel or a prequel,” Greenwell says. “They’re promiscuous with each other,” with events in Cleanness happening before during and after those that take place in What Belongs to You. Each chapter in Cleanness functions as its own stand-alone story. In one, the narrator listens to the painful coming-out tale of one of his students which echoes back to his own doomed first love. In another, he meets his friends for a political protest and witnesses comradery, hope, and an incident that reminds him of the incredible precariousness of peace. In the central chapters of the novel, we witness the narrator fall in love with R, a fellow closeted man he meets online, with whom he experience new levels of trust and intimacy. We also watch the narrator engage in a sexual encounter with a stranger that nearly ends in his death. But each chapter continues to twist and complicate any easy judgements we might make about the characters we meet. And in turn it asks us to make room for contradiction and change in our own lives and to look at each other, not as heroes or villains but as humans.

Though he is best known for fiction, Greenwell got his start as a singer, having trained in opera beginning in high school, before moving on to poetry, criticism, and essay writing. Having moved back to the United States in 2013, he continues to balance a life of writing with a life of teaching in Iowa City, where he is a visiting professor at the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

I spoke to Garth shortly before his book’s release about the uneasy marriage of capitalism and sex, the future of democracy, and, of course, love.

What I love so much about this book—and your writing in general—is how little you moralize sex that includes pain or violence or an embodiment of a kind of toxic masculinity. You leave readers feeling like maybe this kind of sex is healing, or maybe it reinforces shame, or maybe it’s both, but there’s a lot of breathing room for contradiction.

I think the earliest really explicit piece of the book I wrote was “Gospodar” [which involves a sadomasochistic encounter the narrator has with a stranger in Sofia]. I remember as I was writing that feeling like I really wanted to get at a certain experience of sex that I wasn’t sure I had seen represented, and to get there, it required a commitment to explicitness and a lack of squeamishness and concern about audience. I had to write things that would be off-putting and disturbing to many people. But I wanted this experience of rawness and explicitness to be paired with a very high art feeling and all of the filters of consciousness and literary tradition. That was exciting to me, and I was trying to write in a way that gave me access to both of those things.

I hope that the book doesn’t offer any single message about sex or the kind of sex the narrator seeks out. The argument the book makes is sex is all of those things and sex is always going to present dilemmas that outpace any moral calculus we might bring to them. I think that’s true of a lot of things in human life and that doesn’t exempt us from responsibility or the necessity to hold ourselves accountable but it refuses us the luxury of any too-easy accounting.

It does feel like there is something more self-aware and therefore more connected about the narrator’s sexual relationships in Cleanness.

I believe this is a much more social book than What Belongs to You—there are so many more characters and the narrator has many more relations. I know the bar is set in a different place, but to me this is also a much happier book and there are more moments when someone intervenes in the narrator’s ratiocination and kind of gives him a way out, especially in the central love story with R. In some way the book wants to posit that one of the things love is, is a way of opening a door for the other and giving the other relief.

Is that what you think love is?

I do use fiction to think. One of the things I think narrative can very powerfully do is test ideas in a kind of reality simulation. In What Belongs to You the narrator had previously thought that attention is love, that to look at something and attend to it is a form of love. But he revises that and says love is not looking at someone but looking with someone and facing what they face. And it led me to a moment where I was like, I do think that’s true.

I feel like it will be years before I know whether something similar happened with this book, but I do think that one of the things we do as lovers is recontextualize one another’s lives. I would not want to turn it into something tritely optimistic—and I’m always skeptical of open doors or whether an open door will ever lead anywhere other than another room that will eventually feel as stifling as the ones we were in before—but that experience of opening out to someone else is exhilarating.

You mentioned “Gospodar,” which was originally published as a stand-alone story, as were some of the other chapters in this book. I’m curious how you approached structuring those pieces, because the book feels so seamless.

There was a lot of revision. There were surface-level revisions of repetitions across previously published pieces that I took out, but then the big question was putting the pieces in relationship in the larger structure and figuring out how time would work across the book as a whole. I knew I didn’t want the book to be chronological. I wanted there to be relationships that were more mysterious and out of time. But then I wanted something chronological at the heart of the book. It felt important to me for the three R chapters, and for that central love story to have a beginning and a middle and an end. But then the first and third parts I found myself realizing I wanted to have a kind of mirroring structure, where they were resonating with each other but also showing very different reflections of the narrator and his experiences in Sofia.

And then when it came time to put a label on the book there was the question of what we called it. Is it a novel? Is it a story collection? I finally felt like neither of those were right to me. Cleanness really feels, to me, like a book of fiction which is how FSG is publishing it, which makes me really happen and readers can think of it however they want.

I know it’s been a while since you wrote poetry, but do you think poetry allows you to make bolder structural choices with fiction?

I very much feel that poetry is akin to sculpture, and that I was carving language out of silence and trying to exempt language from time. I wanted to take a thought and make it suspended in white space. But that eventually came to feel kind of stifling to me. I sweated so much over individual words and over feeling like I had to choose the words that would kind of open in this infinite way and be infinitely resonant, and in prose I don’t feel the same anxiety about finding the precise single word because I’m so often drawn to syntax that says this or this, or some combination of this and this and this. I think both of those strategies [in poetry and prose] are after the same thing, which is amplitude and resonance. But the reason I’ve kept writing prose and haven’t yet returned to poetry, although I would love to, is there’s something exciting and surprising about the very un-sculptural movement that the kind of sentences I’m drawn to allow for.

There’s a kind of musicality in your prose, I think. The way the words rise and fall, the kind of drama of each sentence. I know you were an opera singer in your younger life, do you feel like you take that practice to the page, too?

Music is endlessly inspiring to me. I don’t listen to music when I’m writing but I reach for musical analog for an effect I want in writing. Because of the training I had in the Bel Canto tradition, one of the lessons I take with me into writing is the fact that language is something that exists in our body. It has materiality and corporeality. And in a way that’s not so different from poetry; opera can show you the way that emotions can be generated by suspending language in time. An aria takes very few words and suspends them over great distances, and there’s a way in which that itself becomes a kind of expression or embodiment of desire.

But I also find inspiration in painting, film, theater, dance. Sometimes a particular artist becomes crucial to a project. My partner is Spanish, and we were in Madrid while I was editing What Belongs to You. There was a wonderful El Greco exhibition at the Prado, and I went almost every day, usually sitting for an hour or so in front of a single painting. I can’t really articulate why, but it was helpful. Maybe it’s that El Greco’s paintings so often seem to make artistic struggle visible; sitting with them gave me a weird sense of solidarity.

What is your writing schedule like? Is that something that also gives you a sense of solidarity?

When I was working as a high school teacher, the only way I could be productive was to have a strict schedule: I wrote from 4:30 to 6:30 every morning. I still like to write first thing in the morning. Routines are important for me, and I find it hard to work well when I’m in an unsettled situation: traveling, say. My partner and I bought a house recently, and my writing room is the garage, which the previous owner converted into an artist’s studio. On warm days, if I keep the door open, a neighbor’s cat will come in to say hello: the best distraction.

I also can’t work with a word or page count: It makes me miserable to feel that I have to meet some metric of productivity. Anytime I have a deadline it takes over my life; I hate deadlines. The only metric that matters for me is time: I have to be at my desk, doing nothing else, for a certain amount of time. I write by hand, and keep all screens in another room. I tell myself that it doesn’t matter if I don’t write a word: As long as I sit with my notebook for a certain number of hours, I’ve done my work.

To go back to what you said about Cleanness being a “more social” book, I also think this book gives a larger sense of what it takes for gay men to navigate relationships in Sofia. Has the situation for LGBT folks in Bulgaria in general changed or improved since your time there?

I don’t want to pretend to speak about that authoritatively because I do feel further and further away from life on the ground. When I was teaching at the American College of Sofia (ACS), I and a few other faculty members and a very passionate group of students tried to start a Gay Straight Alliance, and that was stamped out by the administration. So we had a club that was about human rights in a kind of generic way that was really a gay club even though we couldn’t call it that. But, shortly after I left, the campaign was continued by Garrard Conley, author of the book Boy Erased, and other faculty. And a couple years ago ACS became the first high school in the Balkans with a GSA.

At the same time, my sense is that the increasing influence of Putin in that part of the world has made gains achieved by queer people feel very provisional and perilous. I was in Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013, and for the first three years there was a feeling of incredible progress around LGBT rights and visibility and then around 2012 it felt like this very concerted pushback campaign in which conservative politicians and the Orthodox church began speaking in unison with Putin about gay propaganda. Which, let’s acknowledge, is very much what’s happening in the United States right now on all fronts.

Yes, the protest chapter in Cleanness felt like it contained a really familiar urgency. In what ways have your experiences of political protest in Bulgaria been similar or different to your experiences in the United States?

I had never experienced anything in the United States that felt like what was happening in Bulgaria in 2013 with these enormous street protests across the country. You really did feel like all of Sofia was in the streets. There was also a kind of extremity that I have not seen in the United States. I think it was six people set themselves on fire in protest of conditions, and that kind of public martyrdom is not something we’ve experienced on that scale in the United States. But seeing the kind of misinformation campaigns and meddling on the part of Putin that happened in America in 2016 really felt like a kind of deja-vu. Again, I’m not qualified to make this statement, but it does feel like what Putin has been doing in the West by encouraging chaos is something he had been doing in the area of former Soviet influence for a long time.

What was most surprising to me about the protest scene in Cleanness is that it did not erupt in violence.

One of the things that I wanted to explore in that chapter was the feeling of contingency, that at any moment what is a kind of haloed expression of democracy could become violent and that there were elements really trying to create that chaos. This is something I feel very strongly happening in the United States. I believe in the institutions and traditions of liberal democracy, not because they have ever been perfect but because they offer us the best mechanisms we have ever devised as human beings for addressing wrongs. It terrifies me how close we are to the brink of letting those institutions fall away and how that is a crisis coming from all sides.

I think there is active malevolence and an active desire to destroy those institutions in favor of a kind of authoritarianism and state violence coming from the right. And then from the left I think there is an entire loss of faith and confidence in the idea that those institutions are worth defending. There’s a way in which the central question of the chapter about the protest is a question that I feel very much in America right now, which is: Where do we look for a unifying story or vision? Where do we look for a story we can tell about ourselves that feels adequate to our history and also enabling of a future?

It’s interesting to think, if our structures of government and our relationship to power and capitalism were different, how would the sex we have be different?

Yeah, one of the things that wasn’t talked about much with What Belongs To You was the intersection of the body and economics. How we inhabit our bodies, how we have sex happens in a context, and that context is ideological and economic and political and historical. Sex in a Soviet-style apartment block in Sofia is not exactly the same phenomenon as sex in an Italian city or sex in a park in Louisville, Kentucky.

But I’m also always trying in fiction, and of course one can only fail, to show how erotic relationship is structured and conditioned by politics and economics but not exhausted by them. I refuse a sense of human life as merely determined by these larger structures. To me, fiction lives in the relationship between those larger structural forces and human agency. That space, which is not exactly a space of freedom but is not a space that is foreclosed or fully determined.

That’s one of the most convincing arguments I’ve heard for why someone should be a writer.

[Laughs.] Well, almost all of our lives and thinking exist in spaces of ambiguity, uncertainty and doubt. And yet in much of our public speech and all of our political discourse we use language in a way that wants to deny all of those things. Art seems to me precisely the tool we have for allowing ourselves the fullness of human thinking.

Amy Gall’s work has appeared in Tin House, Vice, Glamour, Women’s Health, the anthology Mapping Queer Spaces, and elsewhere. Recycle, a book of her collages and text, coauthored with Sarah Gerard, was published by Pacific Press in 2018. She is the recipient of a MacDowell Colony fellowship and earned her MFA in creative writing from the New School. She is currently working on a collection of linked essays about queer bodies, sex and pleasure.